|

|

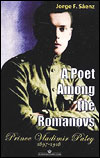

On January 10th (December 28th by the old calendar) we commemorate the worldly birthday of Royal Martyr Prince Vladimir Paley, one of the so-called “New Martyrs of Alapayevsk,” – a group of royal martyrs heinously murdered by the godless Bolsheviks on July 5/18, 1918, on the day following the equally brutal murder of Tsar-Martyr Nicholas II and his family. Since the holy Prince Vladimir is somewhat less known than the other royal martyrs, it is truly by God’s Providence that we have been granted greater knowledge of the saint and his martyrdom from an extraordinarily wonderful biography of him, entitled "A Poet Among the Romanovs", written by Jorge Francisco Saenz Carbonell and published in 2003-2004 by the European Royalty History Journal from Oakland, California. The English version can be purchased through ERH Bookstore ($25.00 + shipping) by contacting them via e-mail: eurohistory@sbcglobal.net. In Europe the book is being sold at Royalty Digest (UK), Librairie Galignani (Paris) and van Hoogstraten English Bookstore (The Hague).

|

|

The author, Jorge Saenz, was born in San Jose, Costa Rica. He is a professor of the History of Law in the University of Costa Rica, and also teaches Diplomatic History of Costa Rica in the Costa Rican Foreign Service Institute. He has published several books in Spanish, mainly about Costa Rican juridical, diplomatic and political history. The author first became interested in Prince Vladimir after reading an autobiography written by the latter’s half-sister, the Grand Duchess Maria. Later, coming across further material on the Prince, he became fascinated by the life and work of the young martyr, his strong faith, his talent, as well as terribly shocked by the way he and his relatives were murdered in Alapayevsk. Being deeply moved by the Prince’s writings, the author felt a desire to let more people know what a talented writer and marvelous human being he was, which led to the writing of this exemplary biography.

The author has most kindly given us his permission to use excerpts from his book to compose a saint’s life of the Royal Martyr Prince Vladimir Paley. The chapter on the final martyric journey and death of the New Martyrs of Alapayevsk is presented almost fully.

|

|

|

A POET AMONG THE ROMANOVS

|

|

Prince Vladimir Paley, first cousin of the last Tsar, was a poet among the Romanovs, but not a Romanov. The rules of the Imperial family prevented him from being considered a member of the dynasty, due to the “unequal” marriage of his parents. This circumstance could have saved his life; however, when he was requested by the Bolshevik regime to deny his beloved father, Grand Duke Paul of Russia, he remained loyal to the ties of affection and honor, and chose captivity and death instead.

He lived only twenty one years on this earth. However, during such a brief life’s journey, he impressed those around him with his extraordinary talents. It was particularly astonishing to see the natural and abundant way in which harmonious, bright verses flew from him, just as it had happened to Mozart with the notes of his musical compositions. Brutally murdered in 1918, when he already seemed called to become one of the great characters of Russian literature, - his poetry, full of passionate feeling, young freshness and sometimes mystic depth, was forgotten for political reasons, while his beloved country lived under a regime of terror of which he was one of the first victims. His only «crime» was to be related to a dynasty of which he had not even been an official member.

|

|

“Volodya was an extraordinary being, a living instrument of rare sensitiveness, which could of itself produce sounds of startling melody and purity, and create a world of bright images and harmonies. In years and experience he was still a child, but his spirit had penetrated into regions reached only by a few. He had genius...”

|

|

|

This was the way Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, daughter of Grand Duke Paul of Russia and his first wife, Alexandra of Greece, spoke of her younger brother in her autobiography Education of a princess, and she was quite right: Prince Vladimir Pavlovich Paley was indeed an extraordinarily gifted character and a most remarkable poet.

Prince Vladimir was born in St. Petersburg on December 28, 1896. He was the son of the Grand Duke Paul, youngest son of Emperor Alexander II, and of Olga Valerianovna Karnovich, the daughter of a chamberlain in the Imperial Court. Since his parents’ marriage was considered to be morganatic, Vladimir could not use his father’s surname of Romanov, but was later granted the title of Prince Paley by a special decree of Tsar Nicholas II.

|

Prince Vladimir with his family

|

Prince Vladimir spent his childhood in Paris, where his parents at first lived in exile after their unauthorized marriage (according to Russian Imperial family law), in an atmosphere of great love and tenderness. Since his early years, it was clear that he was an extraordinarily gifted child. He learned quickly to play the piano and other instruments, and revealed most remarkable skills for drawing and painting. He learned to read and write with similar ability in French, English and German, and later in Russian as well. At a very early age he astounded people by his extensive reading and his extraordinary memory. His elder half-sister Maria wrote:

|

|

“When he was still a baby, there was something indefinable about him that set him apart from the others… His parents saw how different he was from the others and wisely did not try to shape him according to pattern, as had been done with us. They allowed him comparative freedom to develop his unusual abilities.”

|

|

|

|

|

After lengthy negotiations with the Imperial Court, in 1907 the Grand Duke Paul finally succeeded in obtaining Tsar Nicholas II’s pardon for his unauthorized marriage, as well as permission for the whole family to return to Russia. The Grand Duke wanted his son to follow the dynastic tradition of an army career, and in 1908 Prince Vladimir became a student in the Corps-des-Pages, the Saint Petersburg military school for aristocratic youngsters.

Throughout his stay in the Corps-des-Pages, Vladimir continued privately to school himself in painting and music. And it was around 1910 that the young prince started to write poetry, a vocation that he would never abandon. His mother wrote:

|

|

“Ever since the age of thirteen Vladimir had been writing delightful verses… Each time he returned home, his poetic talent displayed itself more decidedly… He availed himself of every free moment to devote his mind to his cherished poetry. By temperament a dreamer, he observed everything, and nothing escaped his subtle, watchful attention… He loved Nature ardently. He went into ecstasy over everything God had created. A moonbeam inspired him, the scent of a flower gave him an idea for a poem. He had a prodigious memory. What he knew, what he had time to read in his short life, was truly marvelous. ”

|

|

|

Poetry was not alien to the Romanov dynasty. One of Paul’s first cousins, the talented Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, was already a distinguished scholar and famous poet, who since the 1880’s published his verses under the name K.R.; several of these were set to music by Tchaikovsky. Vladimir avidly read K.R.’s verses, and several of his own literary creations were deeply influenced by them. From the Corps-des-Pages Vladimir was also well acquainted with two of K.R.’s sons, Konstantin and Igor, who studied there and were later to share his final days and martyric crown.

|

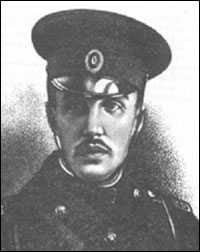

New Martyr Prince Vladimir Paley |

With the outbreak of the First World War, Prince Vladimir, like many young Russians, felt flooded by patriotic enthusiasm, which he expressed often in his poetry. However, hopes for a quick victory soon vanished, and Russia, just as the other fighting countries, found herself involved in an endless, bloody nightmare.

For Vladimir’s class at the Corp-des-Pages, the War meant an accelerated promotion. In December of 1914 he entered the regiment of the Emperor’s Hussars, and in February of 1915 he left to join his regiment. On the day of his departure, he went to an early liturgy with his mother and sisters. Except for them and two hospital nurses, the church was empty. It was a real surprise for Vladimir and his family to discover that the two nurses were the Empress Alexandra and her close friend, Anna Vyrubova. Empress Alexandra had wished to say farewell to Vladimir, and had brought him a little icon and a prayer book.

|

|

Being the son of a Grand Duke didn’t keep Vladimir away from the perils and cruelty of the war. On several occasions he was sent off to make dangerous reconnaissances, and more than once shells and bullets fell quite near him. For his courage he was awarded a military medal, Saint Anne of the 4th Degree. Promoted to lieutenant, he was popular among the soldiers.

|

Grand Duke Konstantin Romanov - "K.R." |

In the trenches Vladimir kept on writing, and along with many verses expressing intimate love feelings and memories, his lyrics began to depict the suffering and destruction caused by the conflict, the blessed work of the sisters of mercy, and the death of dear comrades from the Corps-des-Pages. He also translated into Alexandrine verse in French a famous drama written by Grand Duke Konstantin, The King of the Jews. In April of 1915, while the young soldier was at home in Tsarskoye Selo enjoying a week’s leave, K.R. expressed his wish to hear the translation, and invited the young author and his parents to Pavlovsk. He was already a very sick man, and the high quality of the translation moved him deeply. With tears in his eyes he said: “I have had one of the greatest emotions of my life - I owe it to Volodya. I cannot say anymore. I am dying. I pass on to him my lyre. I bequeath to him my talent as a poet, as though he were my son.” K.R. wanted Vladimir’s translation to be published in France, but the war wasn’t a good time for such projects. Unfortunately, the text was never printed in Russia either, and was lost during the Revolution.

|

|

The October Revolution in Russia and the beginning of the Bolshevik regime marked the first steps of a lengthy calvary for all the relatives of the Tsar who had chosen to stay in Russia. Soon time was running out fast for all the relatives of the Tsar, Romanovs or not. On March 3, 1918, one of the most powerful commissars of Petrograd, Moisey Solomonovich Uritzky, ordered all the members of the Romanov family to present themselves to the city’s Cheka. Since Grand Duke Paul was ill, the family decided that Princess Paley would take a doctor’s certificate to the Cheka, and that Vladimir, who did not bear the name of Romanov, would remain at home, in the hope that he would pass unnoticed. However, the Cheka agents told Princess Paley that Vladimir should present himself the next day.

On March 4th, Vladimir went to the Cheka office in Petrograd. He was received by Uritzky, who made the young poet an insulting offer: “You are going to sign a paper saying that you cease to regard Paul Alexandrovich as your father, and then you will be free at once; if not, you will sign this other paper and that will mean exile.”

|

Prince Igor Konstantinovich |

That was his last ticket to life, but Vladimir was a man of principle. Despite the fact that he was boiling over with rage, he didn’t answer and just kept his gaze firmly fixed on the Bolshevik commissar. Uritzky must have seen such a look of reproach and contempt that he said brusquely: “Very well, then, if that’s how it is, sign your sheet of departure into exile.”

The Princess Paley did whatever she could to save her son from the Cheka’s claws, but it was too late. Her supplications were useless, and she was told that Vladimir was to be at the train station on March 22nd , to travel to Vyatka with other exiled members of the Imperial family – the Princes Ioann, Konstantin and Igor Konstantinovichi, and Grand Duke Sergey Mikhaylovich, together with their faithful retainers.

|

|

In Vyatka, hardly touched yet by the revolution, people were sympathetic to the exiles, bringing gifts and helping them to settle, and nuns from a nearby convent volunteered to prepare their meals. The Bolsheviks became concerned about this growing kindness and immediately decided to transfer the Princes to another town. One day, a group of soldiers came to the house and told the exiles, “The regional Soviet considers that your stay in this town is no longer desirable. Too much kindness has been shown to you. It has been decided to transfer you far away, to Yekaterinburg. You will leave tomorrow with an escort.”

On April 17, 1918, Vladimir’s family in Tsarskoye Selo received a telegram from him, stating that, by order of Moscow, he and his Romanov cousins were all about to be sent to Yekaterinburg. Their stay in Vyatka had lasted only eleven days.

|

|

Yekaterinburg was the capital of the Urals region and one of the strongholds of Bolshevism. Vladimir had bad presentiments and was greatly depressed by the change. “Our best time, that of Vyatka, is over”, - he said. - “It will be worse now every day”. The others chafed him over his dark view of things, but would soon discover how right he was.

Vladimir and his relatives arrived in Yekaterinburg on April 20, 1918, the Friday of the Orthodox Holy Week. They were told that Emperor Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra, and their daughter, Grand Duchess Maria, were already living in Yekaterinburg as prisoners of the local Soviet authorities in the Ipatyev house, seized from a rich merchant. A few days later, on May 10th , the Ipatyev house received new prisoners: the ill Tsarevich Alexis, his sisters, the Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana and Anastasia, and several retainers who had remained loyal to the Romanovs and were allowed to share their captivity.

|

Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich |

|

Unexpectedly, another member of the dynasty came to live with the young princes: the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Fyodorovna, sister of Empress Alexandra. Despite her intense charitable work of many years with the poor and sick in Moscow, she had been forced to leave her convent and sent to Yekaterinburg with two of her nuns. Vladimir and his companions were very eager to make contact with the Tsar and his family, but the regime imposed upon the latter in the Ipatyev house was very strict.

|

|

However, the Ural Soviet soon considered it too dangerous to have the princes in such close proximity to the Tsar. On May 5th, her namesday, Princess Irina Paley received in Tsarskoye Selo a congratulatory telegram from her son, Prince Vladimir, which also announced that he and his fellow exiles were being transferred to Alapayevsk, a small town with unpaved rotten streets, located a hundred and twenty miles away from Yekaterinburg.

The exiles arrived in Alapayevsk on May 7th. Initially, Grand Duchess Elizabeth was probably not too pleased with the idea of sharing captivity with Vladimir. She had never accepted Princess Paley, and her hostile feelings towards her were transferred to her children. However, in Alapayevsk Grand Duchess Elizabeth and Vladimir came to deeply know and love each other. His sister Maria wrote:

|

Grand Duchess Elizabeth |

|

“… Volodya and Aunt Ella in their different ways helped to cheer and support their companions… Volodya was an altogether unusual character, and my aunt and he, before dying the same death, formed a friendship about which he wrote home the most enthusiastic accounts.”

|

|

|

In June, apparently in preparation for their subsequent murder, a prison regime was imposed on the exiles. The Alapayevsk Bolsheviks showed a last glimpse of humanity in not shooting their retainers, as their cronies in Perm and Yekaterinburg had done with several members of the Romanovs’ household, but forced these faithful retainers to leave Alapayevsk. Prince Vladimir’s faithful valet was able to take away with him the last letter Grand Duke Paul and Princess Paley were ever to receive from Vladimir, in which he told them about the sufferings and humiliation the royal exiles were enduring in Alapayevsk, but also remarked on how his faith was giving him courage and hope. He also said:

|

|

“All that used to interest me formerly, those brilliant ballets, those decadent paintings, that new music – all seems dull and tasteless now. I seek the truth, the real truth, the light and what is good…”

|

|

|

|

MARTYRDOM IN AN ABANDONED MINESHAFT

|

Prince Vladimir Paley |

Vladimir and his exile companions spent almost a month under an unbearable prison regime. There would be no improvement: the White Army was reaching the Urals, and the Bolsheviks decided to murder Tsar Nicholas II and all his relatives in the region before they could be rescued by “counterrevolutionaries.” There would be no trial, no charges, just cold-blooded murders. For the Bolsheviks it didn’t matter if the victims were to be sick children like Tsarevich Alexis, or promising young men who had never been involved in politics, like Prince Vladimir Paley and the Konstantinovichi princes.

In the night of July 4/17, Tsar Nicholas II, his wife and children, and their faithful retainers were massacred in the basement of the Ipatyev house, and buried in a secret grave in the forests near Yekaterinburg. The Ural Soviet also decided to kill all the Alapayevsk prisoners.

|

|

Unaware of the atrocious Yekaterinburg massacre, the prisoners in Alapayevsk spent the morning of July 4/17, their last one, in their secluded boredom. At midday, a Chekist by the name of Startsev arrived with several Bolshevik workers, sent away the guards on duty, took from the exiles almost all of their remaining money, and told them that they would be transferred that night to a place about ten miles from Alapayevsk. The Bolsheviks’ real purpose, however, was to take them to an abandoned half-flooded iron mine near the village of Sinyachikha, which had already been chosen as the murder site. The mine had a pit called Lower Selimskaya, almost sixty-five feet deep, where the bodies would not be immediately found.

Late at night they tied Grand Duchess Elizabeth’s and nun Varvara’s hands behind their backs, blindfolded them and took them outside the building, where several carts were waiting. They made them sit in one of the carts and sent them off to their destination, since it was decided earlier that the carts should not leave the town together.

|

|

After the Grand Duchess and her faithful companion left, the Bolsheviks did the same with the men. The Konstantinovichi Princes and Vladimir were taken out into the corridor and blindfolded, then had their hands tied behind their backs and were placed in another cart. Only Grand Duke Serge realized what was going to happen and tried to resist, saying that they were all going to be killed. The Bolsheviks finally shot at him and wounded him in the arm, then put him in the last cart and set off.

Shortly after leaving Alapayevsk, all the carts came together. In the darkness, a group of peasants going to town had a last glimpse of the Princes and their butchers on the road to Sinyachikha. They met a creepy silent column of ten or eleven carts, with two people in each. The Princes were wearing plain civilian clothes. One of the peasants bore witness to the fact that the column proceeded quietly and calmly; the carts made absolutely no sound at all. At about one o’clock in the morning the column approached the mineshaft. It was the 5th/18th of July, which happened to be Grand Duke Serge’s namesday.

|

Grand Duke Sergey Mikhaylovich |

|

Upon arriving near the mine, the prisoners were taken out of the carts and made to walk several hundred yards to the chosen mineshaft. The Grand Duchess Elizabeth sang a hymn as she walked.

As to what happened afterwards, one of the Bolsheviks involved, a certain Vasily Ryabov, offered the following account of the murders:

|

|

“First we led Grand Duchess Elizabeth to the mine. After throwing her down the shaft, we heard her struggling in the water for some time. We pushed the nun Varvara down after her. We again heard the splashing of the water and then the two women’s voices. It became clear that, having dragged herself out of the water, the Grand Duchess had also pulled her sister nun out. But, having no other alternative, we had to throw in all the men also.”

|

|

|

Blindfolded and with their hands tied behind their backs, it was very unlikely that the victims could defend themselves against being hit or try to escape. However, Grand Duke Serge may have made a last attempt to resist, because he was shot in the head.

|

|

Many months after the murder, autopsies of the bodies showed that despite their having been beaten, most of the victims were still alive when they were thrown down the mineshaft. From Ryabov’s testimony it seems that the Bolsheviks expected that the victims, being blindfolded, injured, unconscious, and with their hands tied, would be quickly drowned in the pit, and that there was no need to shoot them individually.

The autopsies also gave evidence of severe traumatic injuries to the skull and brain in all the victims. Prince Vladimir and Prince Igor were almost certainly unconscious from the time of their injuries, since these were particularly severe. Grand Duchess Elizabeth, Prince Ioann and Prince Konstantin may have remained conscious following their injuries, although this would have been for a short period of time only. The injuries described in the cases of the three Konstantinovichi brothers must have been extremely painful and would have made it difficult or impossible to summon help.

|

Grand Duchess Elizabeth |

|

The testimony of the assassin Ryabov is consistent with the belief that most of the victims remained alive after being thrown down the mineshaft, and gives an idea of the cruelty of the executors:

|

|

“None of them, it seems, drowned or choked in the water, and after a short time we were able to hear almost all their voices again.

Then I threw in a grenade. It exploded and everything was quiet… We decided to wait a little, to check whether they had all perished. After a short while we heard talking and a barely audible groan. I threw another grenade. And what do you think – from beneath the ground we heard singing! I was seized with horror. They were singing the prayer: ‘Lord, save your people!’

We had no more grenades, yet it was impossible to leave the deed unfinished. We decided to fill the shaft with dry brushwood and set it alight. Their hymns still rose through the thick smoke for some time yet.”

|

|

|

According to Ryabov, some guards were posted by the mine, while most of the murderers went back to Alapayevsk, where they sounded the alarm from the cathedral bell tower and told the people that the Princes had been taken away by unknown persons. Apparently some people then hinted at what had really happened, but the guards who were watching over the mine prevented them from trying to help the Princes. Other testimonies refer to the continued survival of the victims at the dark bottom of the pit: some peasants who crept to the edge of the pit heard the sound of singing rising from the bottom; others revealed that the Grand Duchess Elizabeth had used a piece of her head scarf to bandage a wound on Prince Ioann’s broken skull.

Although the martyrs died primarily as a result of their terrible injuries, it is also possible that hunger and thirst added to their suffering, after hours or even days at the bottom of the mineshaft.

|

Prince Ioann Konstantinovich |

|

A White army officer wrote that although the circumstances of the murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his family were terrible, they paled in comparison to the crime of Alapaevsk. Some sources said that two of the Alapayevsk executioners became insane due to the hideous nature of the massacre.

After the murder, the Bolsheviks cynically announced that the Princes had been abducted from Alapayevsk by a group of unknown men. News about the “escape” was published in the Bolshevik press in Petrograd, and for about a year the victims’ families believed that the Princes were alive somewhere in Siberia, and fervently waited to hear from them.

But Prince Vladimir Paley and his companions were gone forever, victims of the holocaust that was beginning to spread all through Russia and which would kill millions of people through the remaining decades of the gloomy twentieth century. On July 18, 1918, Russian literature had also lost one of its most promising poets. At the early age of twenty-one, the final verses of one of Vladimir’s poems, Inscription on a grave, became a reality:

|

“His soul with tired wings

will fly up, murdered, to the Creator.”

|

|

Prince Igor Konstantinovich |

Prince Konstantin Konstantinovich |

|

|

|

On November 1, 1981, the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia canonized Tsar Nicholas II and his family, along with all the New Martyrs who have been killed during the Revolution or under the Soviet regime, including the victims of the Alapayevsk massacre. Accordingly, Prince Vladimir Paley was depicted in the icon of the New Martyrs of Russia, painted at the Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, New York. He appears at the left edge of the Imperial family, next to the Konstantinovichi princes, in military uniform and with a roll in his hand.

|

Royal Martyrs |

A hymn from an akathist dedicated to the Alapayevsk victims contains the following words: |

“Rejoice, O venerable martyr Elizabeth, true model of Christian sacrifice!

Rejoice, O Barbara, devoted daughter of thy spiritual mother;

Rejoice, ye who intercede for your compatriots who find themselves amid

suffering and exile!

Rejoice, O Sergius, valiant confessor of the true Faith;

Rejoice, O brethren, equal in number to the Trinity!

Rejoice, O Princes John, Igor and Constantine, who were like unto the

holy youths in the fiery furnace;

Rejoice, O Vladimir, prince and martyr, who foresaw thine own suffering and death!

Rejoice, ye who have washed your souls clean in the streams of your blood;

Rejoice, ye who stand before the Saviour in the ranks of the new martyrs

and confessors!”

|

|

|

After the Communist regime collapsed, the mineshaft near Sinyachikha became the site of religious pilgrimage, and an Orthodox chapel was built there. There, in the middle of the Siberian forest, believers arrive to pay tribute and to show their respect and devotion to the innocent sufferers sacrificed in that terrible summer night of 1918.

Jorge Saenz

|

|

|